A Feast for the Eyes

How Giuseppe Arcimboldo's mastery intertwined Mannerism and with elements of Surrealism and broke the codes of portraiture?

Happy Sunday and welcome back to Giselle daydreams! Today, I decided to write about Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Recently, I’ve been interested to write about Renaissance, and introducing the Italian master Arcimboldo was the perfect manner to dive into my renewed Renaissance curiosity.

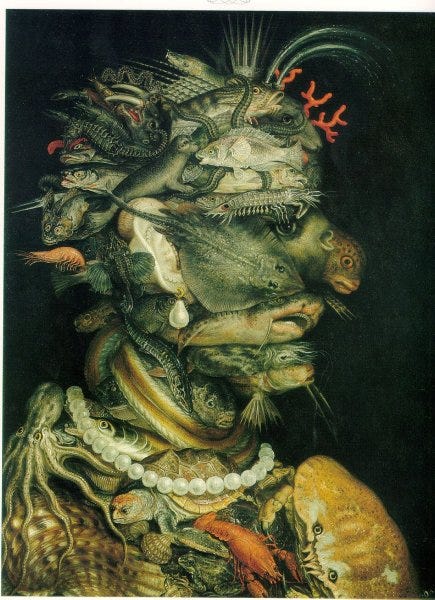

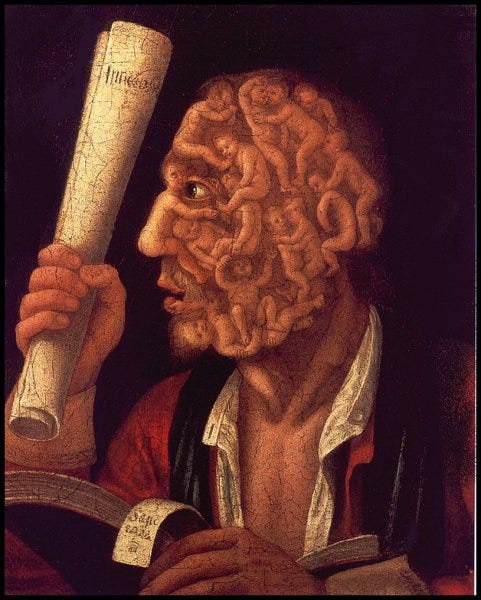

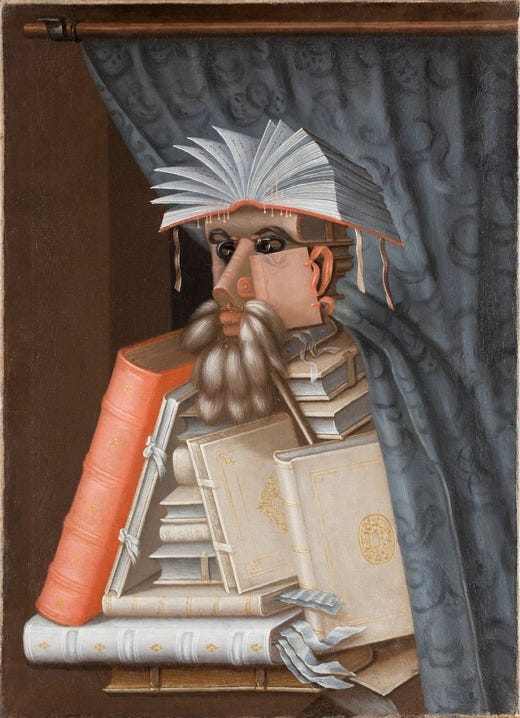

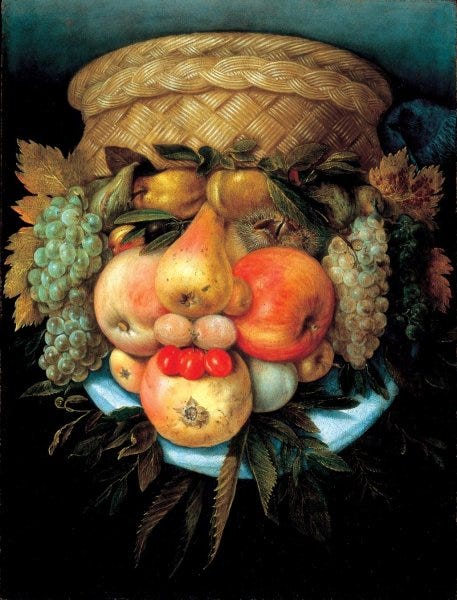

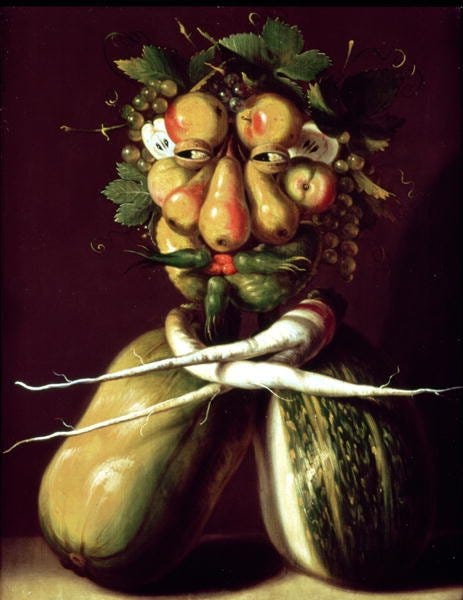

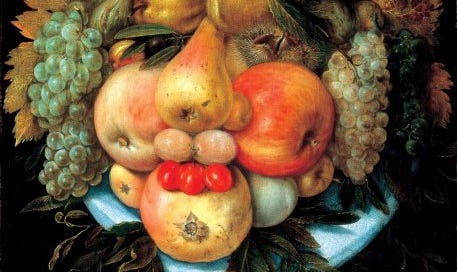

Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526–1593) was an Italian Mannerist painter best known for his fantastical and surreal portraits composed of objects such as fruits, vegetables, flowers, books, and other items. These composite portraits, often representing allegorical figures or seasons, are celebrated for their imagination, technical skill, and symbolic depth.

He served as a court painter for the Habsburg emperors Maximilian II and Rudolf II in Vienna and Prague. As a court artist for over twenty-five years, Arcimboldo was not just a painter; he also served as an event planner. Maximilian II and Rudolf II admired his whimsical and intellectual approach to art. Arcimboldo’s duties at the court extended to engineering projects and inventive designs for fountains and other mechanical marvels. He designed elaborate pageants, costumes, and theatrical productions for the Habsburg court, blending his artistic skills with entertainment and propaganda. This multifaceted talent further highlights his Renaissance versatility.

Before becoming famous for his imaginative composite portraits, Arcimboldo worked on traditional projects, including designing stained glass windows for Milan Cathedral and frescoes for churches. These works were more in line with the Renaissance style of the time. Arcimboldo’s works often reflected the Renaissance obsession with cataloguing and understanding the natural world. His composite portraits can be seen as playful yet systematic representations of botanical and zoological studies, a nod to the scientific advancements of his era.

Arcimboldo's paintings were some of the earliest examples of pareidolia, where the mind perceives familiar patterns (like faces) in unrelated objects. His use of this technique predates the psychological theories that would later describe it.

Arcimboldo as a Mannerist

Mannerism emerged in the late Renaissance and is characterised by its sophisticated, intellectual approach, as well as its emphasis on artificiality, elongated proportions, and complex compositions. Arcimboldo's work epitomises many of these qualities, though he stands apart due to his uniquely imaginative and surreal interpretations, and his work was a precursor to Surrealism.

Mannerist artists often moved away from the naturalistic realism of the High Renaissance, instead embracing artifice and exaggeration. Arcimboldo’s composite portraits, made up of objects like fruits, vegetables, animals, and books, demonstrate this tendency. They are meticulously crafted but deliberately unnatural, playing with the viewer’s perception.

Mannerism prized intellectualism and symbolism. Arcimboldo’s works, such as The Four Seasons (1563,1572, and 1573) and The Four Elements (1566), are layered with allegories. The Four Seasons not only represent the changing cycles of nature but also align with Habsburg ideals of imperial power and continuity; whereas The Elements symbolise the harmony of the natural world under divine or imperial control.

Mannerism often explored distortions and unusual perspectives. Arcimboldo’s art, transforming everyday objects into portraits, exemplifies this experimental spirit. His work The Cook (c.1570) is a trompe-l'œil masterpiece that changes meaning when flipped. This reversible image can be viewed upside down. Upright, it appears to be a dish of roasted meat, but when inverted, it reveals a man’s face. This demonstrates his playful manipulation of form.

Mannerist art is known for its intricate detailing. Arcimboldo’s works are astonishingly detailed, with each object in his composite portraits carefully chosen and rendered to contribute both visually and symbolically to the overall image.

Mannerism flourished in aristocratic and royal courts, where its intellectual complexity and refined aesthetics found favour. Arcimboldo’s position as a court painter to the Habsburgs placed him at the heart of this cultural movement, where his whimsical yet learned art delighted his elite patrons.

While Arcimboldo shared Mannerism’s love for complexity and sophistication, his art’s surreal quality sets him apart. His fantastical creations anticipate the dreamlike imagery of later movements like Surrealism. Unlike many of his Mannerist contemporaries, who focused on religious or mythological themes, Arcimboldo’s works often celebrated nature, science, and the human mind's capacity for invention.

Arcimboldo as a precursor to Surrealism

Arcimboldo is often considered a precursor to Surrealism, the 20th-century artistic movement which explored the unconscious mind, dreams, and the irrational. Although Arcimboldo worked during the 16th century, his imaginative portraits made of objects like fruits, flowers, and books resonate strongly with Surrealist themes and aesthetics.

A hallmark of Surrealism is the combination of unrelated or incongruous objects to create something both familiar and strange. Arcimboldo’s portraits, composed of disparate items, such as a face made entirely of vegetables in The Vegetable Gardener (ca.1587-90), achieved this effect centuries before Surrealism emerged.

Arcimboldo’s composite portraits blur the boundaries between reality and fantasy, much like the dreamscapes of Surrealist artists such as Salvador Dalí and René Magritte. His works invite the viewer into a world where ordinary objects take on extraordinary, symbolic forms.

Furthermore, Arcimboldo’s art relies on pareidolia, the psychological phenomenon where the mind perceives familiar patterns (like faces) in unrelated forms. Surrealists often exploited this tendency to challenge perceptions of reality.

Surrealism sought to destabilise the viewer’s understanding of the world. Arcimboldo achieved this by transforming everyday items into lifelike portraits, creating a sense of wonder and unease. His reversible images, like The Cook, which can be flipped to reveal two entirely different subjects, are early examples of such subversion.

Surrealists explored the unconscious and hidden layers of the mind. While Arcimboldo did not explicitly address psychoanalysis (which came much later), his works can be interpreted as exploring identity and perception through their composite nature, suggesting multiple layers of meaning.

Surrealist artists openly admired Arcimboldo’s ingenuity. Salvador Dalí, for instance, praised his works as an early example of the surreal, and Max Ernst drew inspiration from his imaginative use of natural forms. Arcimboldo’s art was rediscovered and celebrated during the Surrealist movement, cementing his status as a spiritual ancestor to their ideals.

One of Arcimboldo’s most famous works, Vertumnus, a portrait of Emperor Rudolf II as the Roman god of seasons, gardens, metamorphosis and abundance, symbolised the emperor's supposed harmony with nature and his role as a wise ruler. This portrait also encapsulates his proto-Surrealist qualities. The painting's use of fruits, vegetables, and flowers to construct a human likeness mirrors the Surrealist fascination with metamorphosis and the interconnectedness of the natural world and the human psyche. Vertumnus exemplifies Arcimboldo’s skill in creating composite portraits and is a masterpiece of allegorical and symbolic art.

The quirky nature of his works was not only for aesthetic purposes; it was a form of intellectual humour that delighted his patrons. His ability to turn mundane objects into faces was considered both amusing and ingenious. Arcimboldo’s success made composite portraits fashionable in the Habsburg court. Other artists began to imitate his style, though none achieved his level of intricacy and creativity.

Arcimboldo’s oeuvre fell out of favour after his death in 1593 and was largely forgotten for centuries. His works often carried deeper allegorical meanings, reflecting the Renaissance fascination with the natural world, science, and human ingenuity. However, Arcimboldo was rediscovered centuries later by the Surrealists in the twentieth century, and he influenced artists like Salvador Dalí. This latter revived interest in Arcimboldo’s imaginative style, seeing him as a kindred spirit who blurred the boundaries between reality and fantasy. Arcimboldo’s playful yet profound exploration of identity, nature, and illusion places him firmly within the lineage of Surrealist art. His works remain a testament to the power of imagination, challenging viewers to see the world differently.

Thank you for reading this post. If you enjoyed it, please like, comment, share and subscribe. It helps the newsletter grow.

Thank you for this great article and making me discover a new artist I didn’t know about. Every week, I look forward to reading your articles.

My big takeaway from this piece is based upon the old adage, “Write/Paint What You Know.” I hadn’t realized he had been an Event Planner and master of ceremonies type for royalty and the Court, whereby the detailed arrangements and presentation means everything. Suddenly his attention to such nuance in his playful still life portraits makes even more sense. Who knows? He probably did them as table centers from real edibles and objects before coming to his system of painting them 🤷🏻♀️