Leonor Fini: the Defiant Dreamer of Surrealism

Redefining Femininity, Power, and Eroticism in the Avant-Garde

Happy Sunday and welcome back to Giselle daydreams! Sorry for being absent the last few weeks. Launching my own business is taking a lot of my time, and I didn’t have the opportunity to think about a good post to write. If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while, you know that I love writing about Surrealism. Therefore, I decided to feature today Leonor Fini, the Antagonist Surrealist.

This post is too long for your mailbox, please move on your browser or via the Substack app to read the entire post.

I paint pictures which do not exist and which I would like to see. — Leonor Fini

Leonor Fini remains one of the most enigmatic and subversive figures in twentieth-century art. Though often associated with Surrealism, she was never formally part of the movement, resisting its patriarchal structures while embracing its ethos of dreamlike distortion and psychological complexity. Fini’s work, rich with themes of metamorphosis, feminine power, and erotic ambiguity pushed the boundaries of the surreal, carving out a unique and defiant space for female creativity in a male-dominated avant-garde.

Born in Buenos Aires in 1907 and raised in Trieste, Italy, Fini’s artistic vision was shaped by a fiercely independent upbringing. Unlike many of her contemporaries, she did not study art in any formal setting but instead cultivated her skills through personal exploration and exposure to European masters. By the 1930s, she had moved to Paris, where she encountered the Surrealist circle, including André Breton, Max Ernst, and Salvador Dalí. Though her art resonated with the movement’s dreamlike and psychological depth, Fini rejected the strict ideology of Surrealism, particularly its objectification of women as muses rather than creators.

Breton’s Surrealism frequently depicted women as conduits to the unconscious, placing them in passive or fetishised roles. Fini, in contrast, asserted female agency, portraying women as dominant, mystical, and sovereign figures. Her refusal to be categorised within Surrealism’s rigid framework speaks to her broader resistance to any form of institutional or ideological constraint.

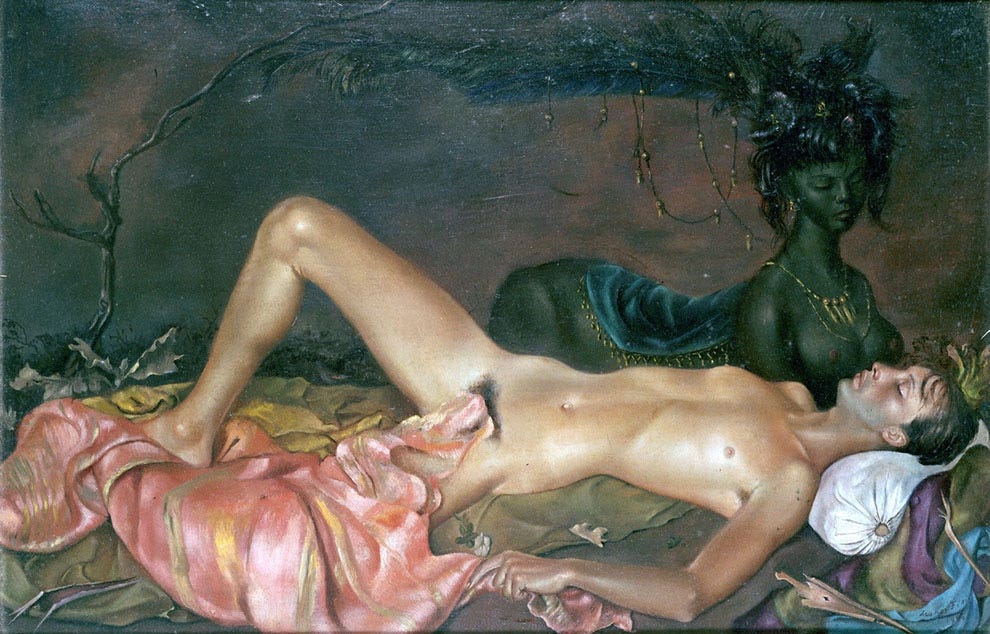

Fini’s paintings often depict powerful female figures, feline hybrids, and masked identities, alluding to themes of transformation, eroticism, and autonomy. Works such as The Guardian of the Phoenix (1941) and Sphinx Amalburga (1942) depict women in positions of control, blending human and animal characteristics to challenge traditional gender roles. The sphinx, a recurring motif in her work, embodies both seduction and menace, suggesting a femininity that is neither passive nor fully knowable.

Unlike the disembodied, fragmented female figures often seen in Surrealist works by male artists, Fini’s women command the viewer’s gaze. They are neither subjugated nor merely symbolic; they are subjects in their own right. This emphasis on female autonomy aligns with later feminist discourse, even though she never explicitly identified with feminist movements.

Eroticism is central to Fini’s work, but unlike her male Surrealist counterparts, she does not depict women as passive objects of desire. Instead, her art explores a fluid and often ambiguous eroticism, where power dynamics are constantly shifting. In paintings such as The Alcove (1941) and End of the World (1949), Fini portrays androgynous figures, intimate embraces, and scenes of sensual ambiguity, suggesting a rejection of fixed identities and conventional binaries.

Fini herself lived a life that mirrored her art’s rejection of traditional constraints. She eschewed monogamy, maintaining relationships with both men and women, and surrounded herself with a circle of lovers, friends, and artistic collaborators. Her personal mythology, crafted through her elaborate self-presentation and refusal to conform, reinforced the themes of multiplicity and transformation that permeated her work.

Paintings, like dreams, have a life of their own and I have always painted very much the way I dream. — Leonor Fini

Despite her prolific career, Fini’s contributions have often been overshadowed by her male contemporaries. Unlike Dalí or Magritte, she did not conform to a singular, recognisable style, making her work less easily marketable. Yet her influence can be seen in later feminist and queer artistic movements, which similarly challenge notions of identity, desire, and power.

Today, as art history re-evaluates the contributions of women within modernist movements, Fini’s legacy is being reassessed. Her defiance of categorisation, her celebration of feminine power, and her rejection of objectification make her a pioneering figure whose relevance extends far beyond Surrealism. In a time when the art world increasingly values multiplicity and fluidity, Fini’s work stands as a testament to the boundless possibilities of artistic and personal identity.

Leonor Fini was never merely a Surrealist; she was a visionary who transcended movements, labels, and limitations. Her work challenged gender norms, redefined eroticism, and carved out a space for female agency in an art world that often sought to diminish it. Fini was Surrealism's defiant visionary, the one who defied Surrealist’s canon and used the subversive power of femininity in her work. In reclaiming her place in the history of modern art, we recognise not only her technical brilliance but also her radical insistence on the right to self-definition, a principle that remains as vital today as it was in her time.

I always imagined I would have a life very different from the one that was imagined for me, but I understood from a very early time that I would have to revolt in order to make that life. Now I am convinced that in any creativity there exists this element of revolt. — Leonor Fini

FIN.

Thank you for reading this post. If you enjoyed it, please like, comment, share and subscribe. It helps the newsletter grow.

Wow wow wow. Came to your post through notes and am completely blown away. It's a crime that this artist's work is not more widely known. F**K Magritte.

That was amazing, Giselle! How has Fini been “lost” or forgotten about for so long? Thanks for sharing this story and her beautiful work. I love the “Ends of the Earth” (I know I’ve gotten the title wrong).💕