Beyond mad love: Jacqueline Lamba, a Surrealist in her own right

Deep dive in another Surrealism’s overlooked artist and the marriage that tried to define her

This post is too long for your mailbox, please move on your browser or via the Substack app to read the entire post.

For those interested in my other projects and links:

Fashion brand | Instagram | ShopMy

Hello everyone and welcome back to Giselle daydreams! Today, I’m back writing about Surrealism and Jacqueline Lamba, an overlooked artist you may or may not know much about. Lately, I’ve been enjoying researching and writing about artists whom I didn’t study in depth while I read art history at university, and I find it very rewarding to keep learning and discovering fascinating stories thanks to writing this newsletter. Without further a due, let me introduce you to the woman who dared to be more than André Breton’s muse and inspiration.

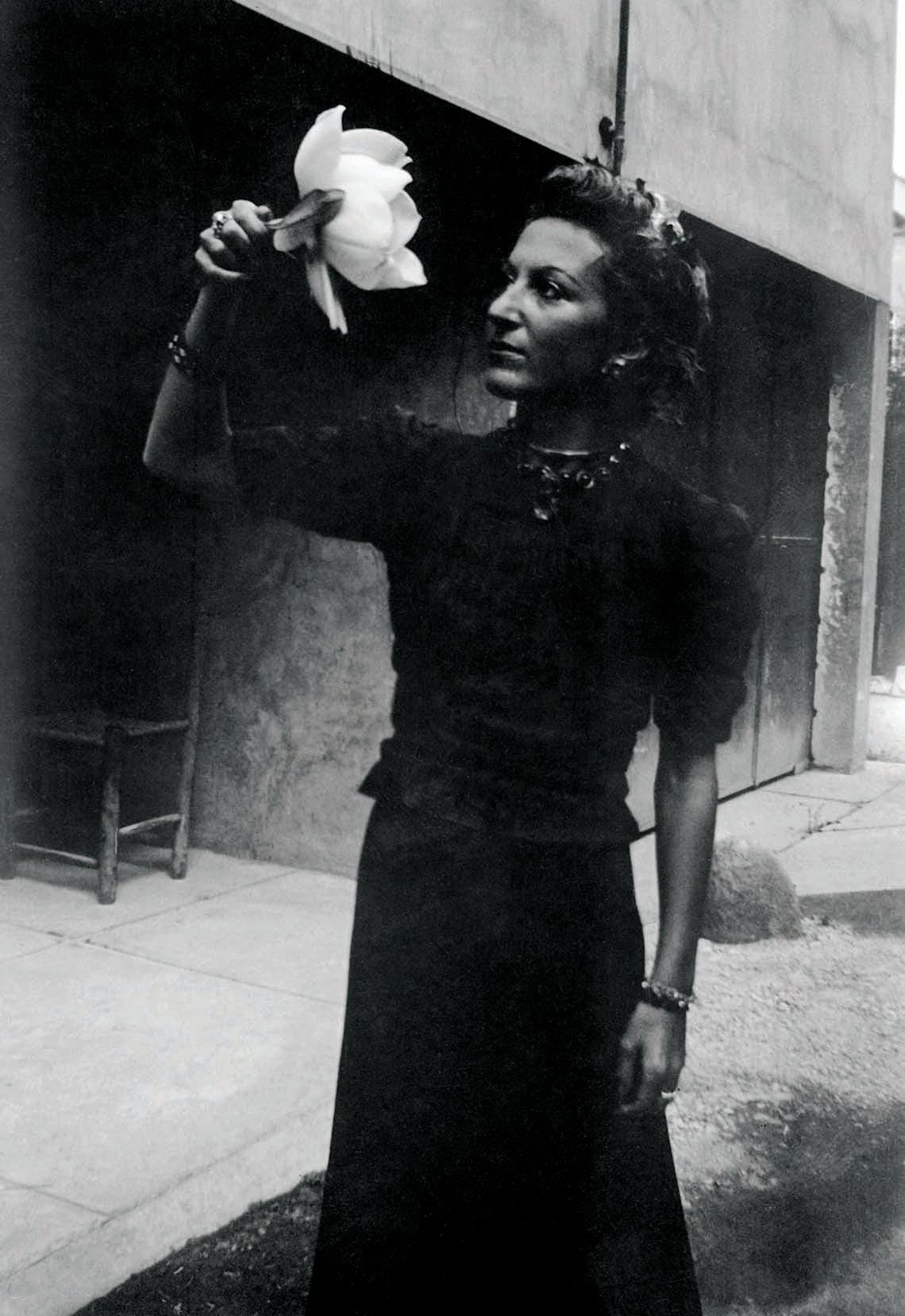

In the grand narrative of 20th-century surrealism, Jacqueline Lamba has often been cast in the shadow of her husband, André Breton—the movement's magnetic leader and author of the Surrealist Manifesto. Their marriage, a union of artistic temperaments and poetic aspirations, is remembered through his lens, immortalised in writings like Mad Love (L’Amour fou), where Lamba is transformed into the quintessential surrealist muse: unknowable, ethereal, and idealised. But Jacqueline Lamba was far more than a passive inspiration. She was an artist in her own right—fierce, experimental, and quietly radical—whose own creative vision challenged the confines of a movement that often romanticised women while denying them artistic agency.

Born in 1910 in the Paris suburb of Saint-Mandé, Lamba came of age during a time of seismic change in art and politics. She studied at the École des Arts Décoratifs, specialising in decorative arts and drawing, and later worked as a lighting designer at the Paris Opera. Her early career demonstrated a deep sensitivity to light, atmosphere, and transformation—concerns that would later echo in her paintings and surrealist collaborations. Unlike many of her male contemporaries, Lamba’s pathway into surrealism wasn’t through polemic or theory, but through lived experience, intuition, and an enduring fascination with the unconscious.

Lamba met Breton in 1934 at the Café de la Place Blanche in Paris. Their encounter, romanticised by Breton as fated and electric, quickly became a cornerstone of surrealist mythology. Breton claimed to have dreamed of her before meeting her; she appeared in his writing as the "woman of fire," the embodiment of automatic desire and irrational beauty. While the surrealists hailed this chance meeting as an embodiment of objective chance—a key surrealist tenet—Lamba herself expressed scepticism about being reduced to a symbol.

Lamba died with the belief that “she would not be recognised as an artist because she was a woman, had been married to André Breton (1896–1966), had stopped painting Surrealism, and had a difficult personality.” (See notes) She thought that “Being a muse is not enough.” This remark encapsulates the tension that defined much of her life within surrealist circles. The movement, while revolutionary in its rejection of bourgeois rationality and its embrace of dreams, myths, and eroticism, often positioned women as muses rather than makers as vessels of male desire, not creators of independent vision. Lamba, like other surrealist women such as Leonora Carrington, Dora Maar, and Remedios Varo, wrestled with this paradox. She occupied a liminal position: central to surrealist aesthetics, yet often excluded from its intellectual authority.

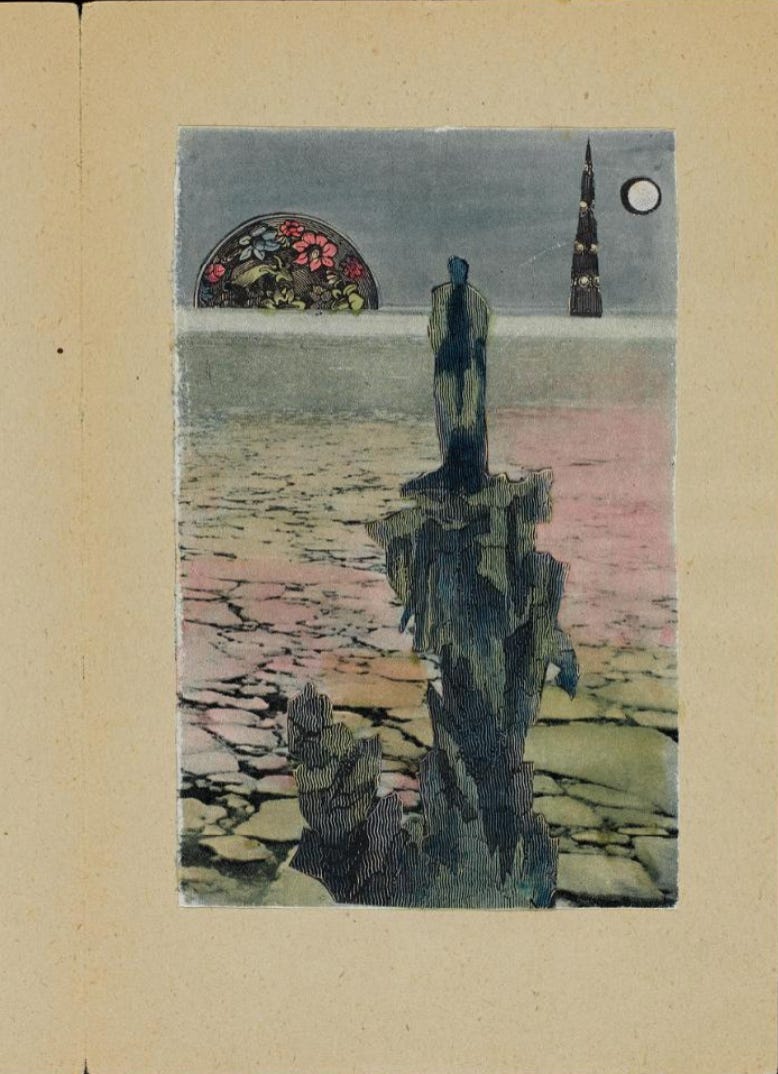

Despite these constraints, Lamba contributed meaningfully to surrealist practices, both visually and conceptually. She participated in group exhibitions, produced paintings and collages, and collaborated with Breton on projects that blurred the lines between poetry and image. Her works often engaged with natural elements—water, light, the moon—and the female body in states of transformation, suggesting a deeply personal and introspective form of surrealism that resisted the patriarchal gaze. In contrast to the confrontational surrealism of some male artists, Lamba’s work was subtler and more atmospheric. It was a surrealism not of rupture but of reverie.

Their marriage, intense and tumultuous, was shaped by both creative synergy and emotional discord. Breton's obsession with romantic idealism—his belief in the "marvellous" woman as salvation—clashed with Lamba’s growing need for autonomy. During the 1940s, their relationship was further strained by the political upheaval of World War II and their temporary exile in New York, where Lamba was exposed to new artistic influences and began to more consciously assert her voice. She mingled with artists like Marcel Duchamp, Arshile Gorky, and Peggy Guggenheim, absorbing the currents of American modernism and becoming increasingly independent in her work.

The eventual breakdown of her marriage to Breton in 1943 marked a turning point. Lamba no longer wished to be enshrined as Breton’s “mad love”; she desired to be seen as a serious artist, unmoored from her role as muse. After their separation, she distanced herself from the surrealist milieu, seeking instead a quieter life of artistic solitude. Her later works, less frequently exhibited and often introspective, reflect this desire for self-definition. Landscapes, aquatic scenes, and dreamlike figures recur, painted in a soft yet penetrating palette. These were not declarations but meditations—a retreat not from art, but from its spectacle.

History has not been kind to Jacqueline Lamba. Like many women artists of her generation, her legacy has been eclipsed by the men with whom she was romantically linked. Yet to dismiss her as merely Breton’s wife or muse is to miss the complexity of her contribution. She challenged surrealism from within—by embodying it, resisting it, and ultimately transforming it into something quieter and more personal. Her art did not scream; it shimmered.

In recent years, a growing scholarly and curatorial interest in overlooked women of the avant-garde has brought Lamba’s work back into focus. Exhibitions have begun to reframe her not as a footnote to Breton but as part of a broader, pluralistic surrealism shaped by women’s lived experiences, desires, and imaginative worlds. In this light, Lamba emerges not as an accessory to history, but as a quiet revolutionary—one who understood the dreamscape not as a stage for male fantasy, but as a terrain for self-invention.

Jacqueline Lamba once wrote, “I do not want to be a shadow, nor the reflection of a flame.” In that refusal lies the core of her artistic legacy: a refusal to be eclipsed, and a determination to glow on her own terms.

Notes: Aube Breton Elléouët (Jacqueline Lamba’s daughter), interview with Salomon Grimberg, October 1999, in Paris.

As always, thank you for reading. Please keep liking, commenting, sharing and subscribing. It helps the newsletter grow and reach like-minded readers.

If you are interested in reading more, the Weinstein Gallery published a comprehensive catalogue.

FIN.

Fantastic read, Giselle! Like so many other women artists, she's been eclipsed by the male artist she was associated with (also thinking of the abstract impressionists of that era - Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, etc.). I'm so happy to see them being brought out into the light! Thank you!