Francis Picabia: The Instigator of Style and the Art of Contradiction

How Francis Picabia disrupted the movements he helped create

Happy Sunday and welcome back to Giselle daydreams! Today I decided to write about Francis Picabia who I consider a chameleon of Modernism and the enemy of orthodoxy. When it comes to his oeuvre, he’s deeply unfaithful to movements, but loyal to provocation, subversion and the art of refusal. He sits in between the Machine and Metaphor but he’s radically inconsistent and that’s why I’m so fascinated by him.

Francis Picabia is a figure whose legacy defies easy categorisation. To study him is to encounter a chameleon of modern art—a man who never settled for a single language, movement, or ideology. Though often overshadowed by his more consistent contemporaries, Picabia's restless energy and artistic subversion placed him at the heart of the three great upheavals of early 20th-century art: Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism. But rather than merely contributing to these movements, Picabia destabilised them from within. He was not a loyal follower but an instigator of rupture, contradiction, and ironic rebellion. Through this lens, Picabia emerges not as a peripheral character but as a key agent in modernism’s interrogation of itself.

Cubism: a brief affair with Form

Picabia's early involvement with Cubism in the 1910s was shaped by his association with artists like Marcel Duchamp and the Puteaux group. His approach to Cubism, however, was never doctrinaire. Where Braque and Picasso stripped forms to their essentials, seeking a rational deconstruction of the visible world, Picabia’s Cubism was looser, more fluid, and emotionally charged. His paintings like Udnie (Young American Girl, The Dance) and Edtaonisl were infused with motion, sensuality, and rhythm; bridging the structural ambitions of Cubism with the kinetic vitality of Italian Futurism.

Yet even in this early phase, Picabia was already sowing seeds of dissent. He saw systems of style as cages, not platforms. Unlike his peers who pursued a linear development of Cubist logic, Picabia treated Cubism as a stepping stone, an idiom to be adopted and discarded. This attitude foreshadowed his central role in Dada, where rejecting fixed meaning would become a mantra.

Dada: the engine of irony

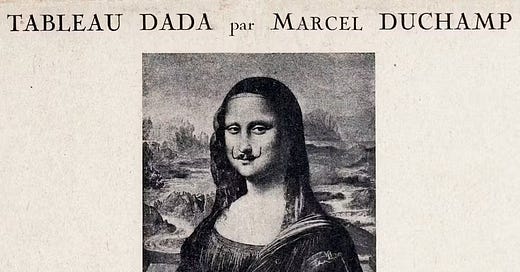

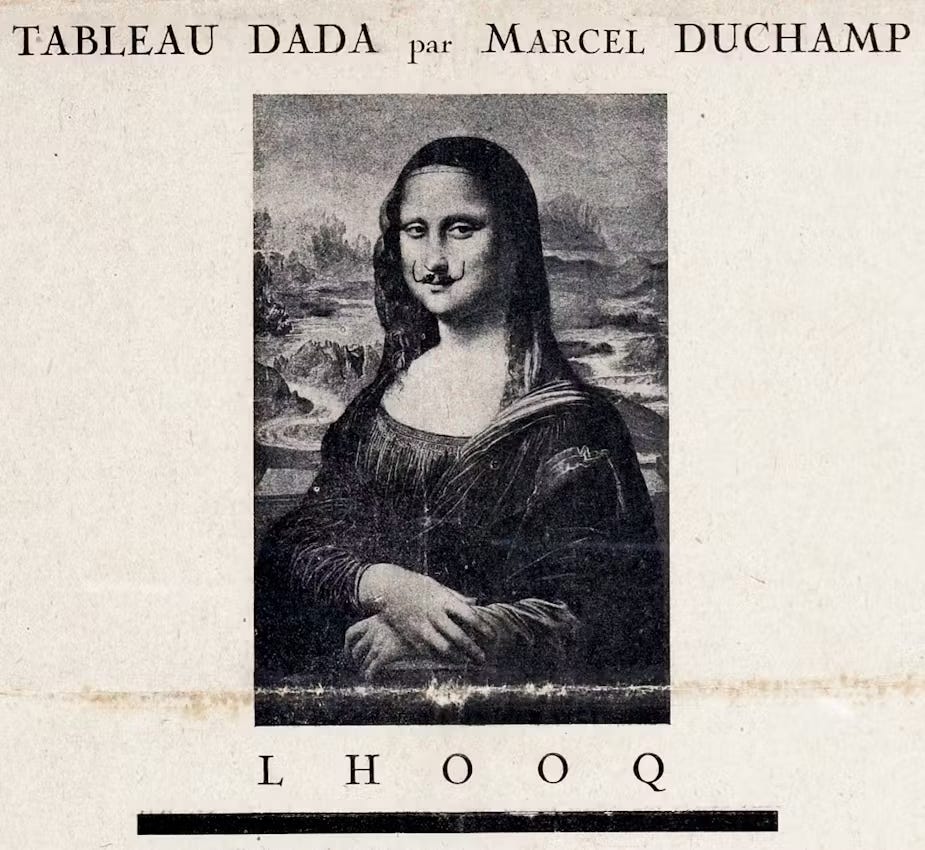

It is in Dada that Picabia’s voice rang the loudest and most provocatively. Alongside Duchamp and Tristan Tzara, he helped shape one of modern art’s most radical revolts—a movement born in the wake of World War I, when the absurdity of violence demanded an equally absurd artistic response. For Picabia, Dada was not just anti-art; it was a weapon of negation. He attacked logic, taste, morality, and the sanctity of the art object.

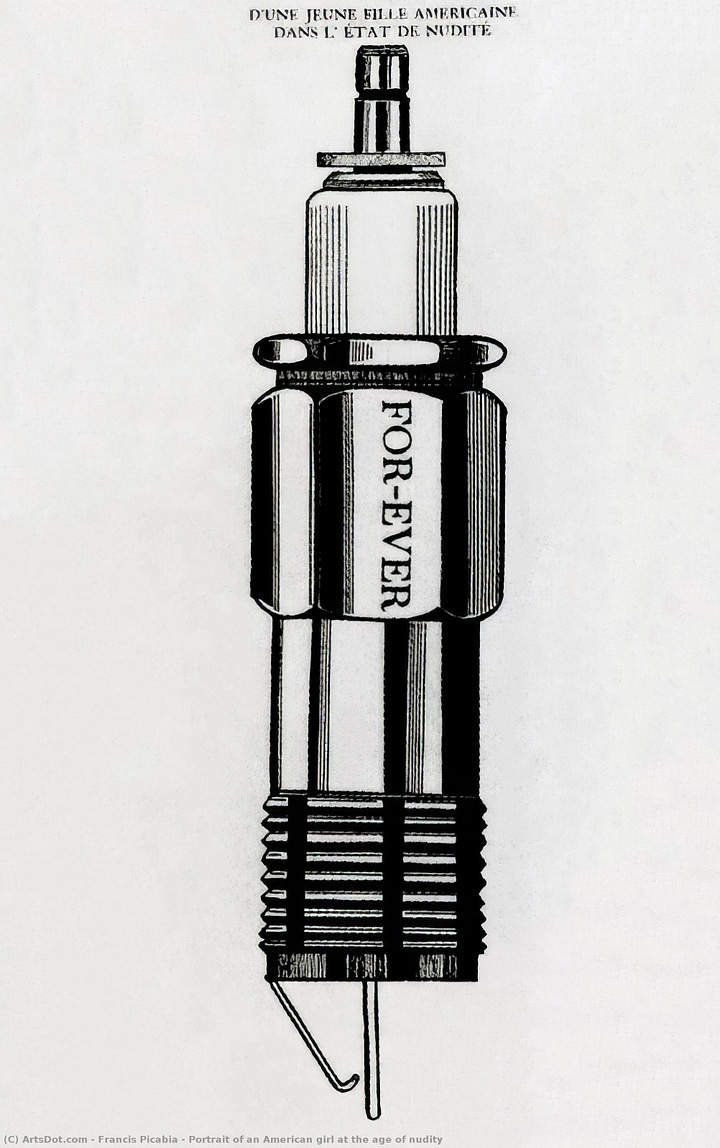

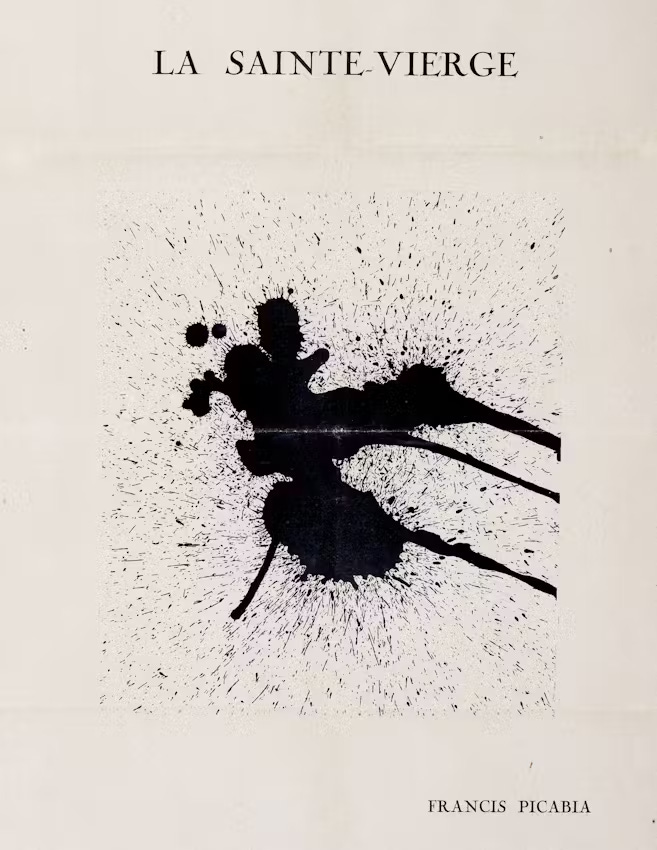

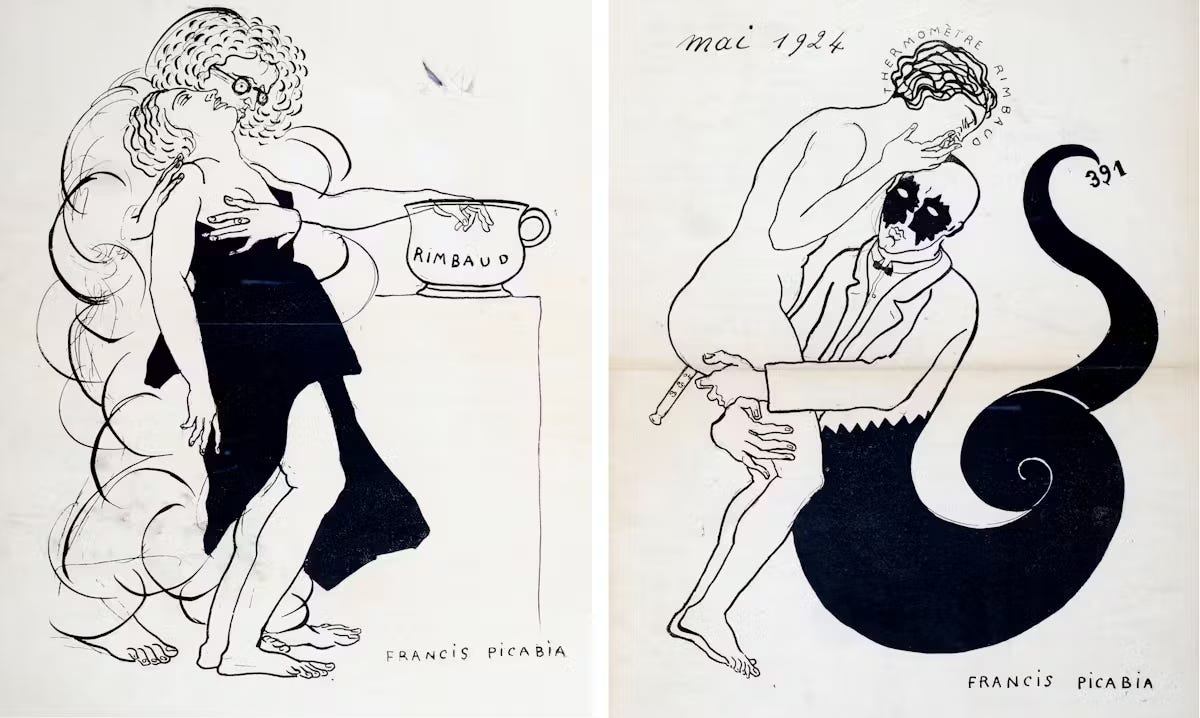

Perhaps his most emblematic contribution was his series of mechanomorphic drawings—machines anthropomorphised in satirical, sexual, and nonsensical ways. Works like Portrait of a Young Girl in a State of Nudity or La Sainte Vierge mock both the sacred and the scientific. These images were not just visual jokes, they were philosophical provocations. In presenting humans as absurd machines, Picabia ridiculed both Enlightenment rationalism and bourgeois sentimentality. He also anticipated postmodern critiques of authorship and meaning by refusing to remain stylistically consistent or ideologically faithful, even to Dada itself.

His magazine 391, published intermittently from 1917 to 1924, became a vital outlet for his irreverent ideas. A mix of manifestos, aphorisms, drawings, and collages that subverted conventional aesthetics. In it, Picabia championed a kind of aesthetic anarchism. He famously declared, "Art is a pharmaceutical product for imbeciles." Such iconoclastic statements weren’t mere provocation, they revealed a deeply philosophical stance on the futility of systems and the illusion of progress in art.

Dada is like your hopes: nothing

like your paradise: nothing

like your idols: nothing

like your heroes: nothing

like your artists: nothing

like your religions: nothing

― Francis Picabia

Surrealism: a troubled affair with the Unconscious

Picabia’s relationship with Surrealism was marked by tension. Although André Breton initially embraced him as a fellow traveller in exploring the irrational and the unconscious, Picabia quickly bristled at the movement’s emerging dogma. He distrusted Breton’s authoritarian tendencies and rejected the idea of automatism as a formula for authenticity. To Picabia, Surrealism threatened to become another orthodoxy; and thus, another enemy.

Nonetheless, some of his works in the early 1920s and 1930s flirted with Surrealist imagery: distorted faces, dreamlike juxtapositions, erotic symbolism. But rather than attempting to probe the unconscious, Picabia used these motifs to parody the notion of inner truth. His Transparencies series layered figurative images—classical nudes, religious icons, and scientific diagrams—into enigmatic compositions that resist interpretation. These works can be seen as critiques of Surrealism’s romanticism, offering instead a visual cacophony of references that reflect the fragmented psyche of modern life.

The devil follows me day and night because he is afraid to be alone.

― Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia was not a builder of movements, he was their saboteur. His greatest contribution to modern art lies not in the development of any single style but in his refusal to be owned by any. He exposed the internal contradictions of avant-garde movements, revealing how easily radical gestures could become institutionalised. In doing so, Picabia anticipated the postmodern strategies of appropriation, irony, and anti-style that would dominate art later in the century.

Critics have long struggled with Picabia’s legacy, seeing him as erratic, unserious, or even cynical. But this is to misunderstand his method. Picabia’s inconsistency was a form of honesty; an acknowledgement that truth in art is always provisional, always contaminated by context, ideology, and ego. His art offers no answers, only disruptions.

Today, in an age saturated with curated personas and brand identities, Picabia’s slippery irreverence feels prophetic. He reminds us that to remain free, an artist must remain unfaithful; not to themselves, but to the very idea of fixed meaning. In the end, Picabia’s greatest work might be his life itself, a performance of endless becoming, where style is both mask and mirror, and contradiction the only constant.

As always, thank you for reading. Please keep liking, commenting, sharing and subscribing. It helps the newsletter grow and reach like-minded readers.

FIN.

I’d never heard of Picabia before your article, so thank you for this window into a “new” artist to me.

I think most of all he was a great artist