Dreams, Disruptions, and the Feminine Gaze: the Radical Vision of Grete Stern

How a Bauhaus-trained photographer used surrealism to challenge gender norms in mid-century Argentina

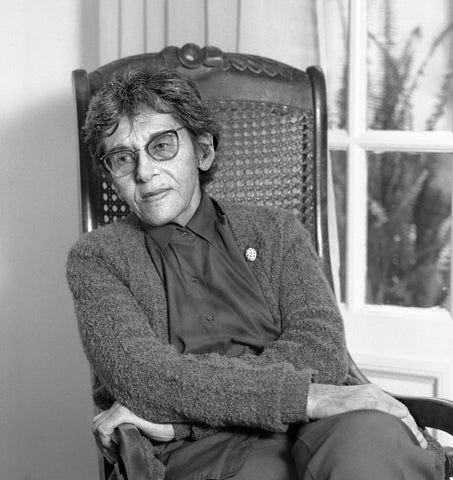

Happy Sunday and welcome back to Giselle daydreams! I think my recent posts could be a collection of essays about overshadowed women artists who are finally being recognised as prominent figures in their own rights. While scrolling on Pinterest and looking for some Surrealist artworks, I came across a photograph that marked me. It was by Grete Stern. Truth be told, I didn’t know about her, or if her name was mentioned to me in my past art history lectures, it was over 10 years and it would have been extremely brief. However, today, I decided to dedicate an essay about her, and I hope that those of you who don’t know about her will enjoy discovering a new fascinating female artist.

This post is too long for your mailbox, please move on your browser or via the Substack app to read the entire post.

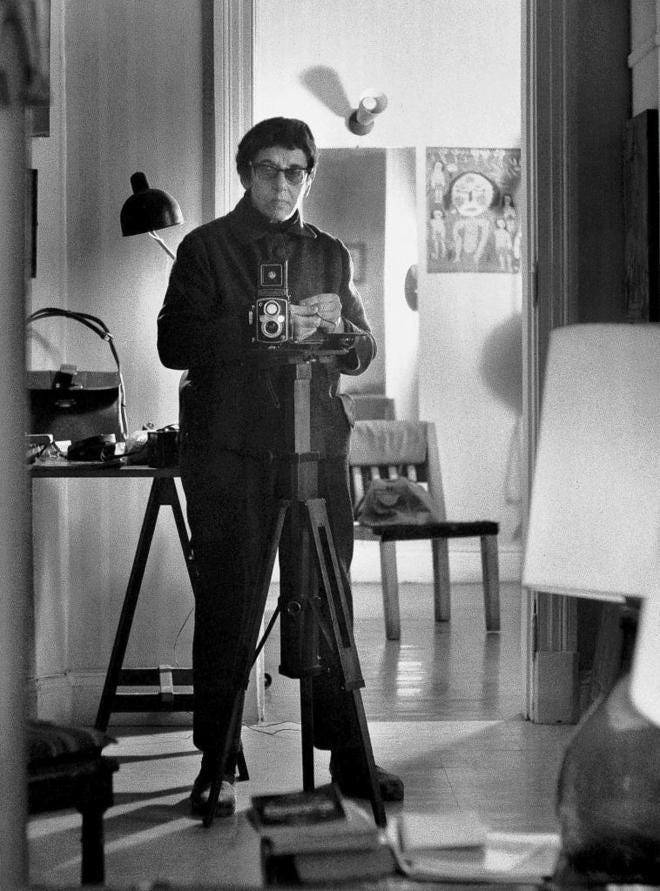

Grete Stern is a name that deserves far greater recognition in the history of photography and feminist art. A German-born artist trained at the Bauhaus, Stern’s work blends the precision of modernist design with the subversive dreamscapes of surrealism. Her most powerful and enduring project, Los Sueños (The Dreams), is a radical critique of the constraints placed upon women in mid-century Argentina. Through photomontage, Stern transformed ordinary magazine illustrations into haunting narratives of entrapment, desire, and defiance, making the subconscious fears and aspirations of women startlingly visible.

Stern’s artistic sensibilities were shaped in the avant-garde environment of the Bauhaus, where she studied graphic design and photography. She was deeply influenced by the school’s emphasis on interdisciplinary experimentation, particularly in her use of photomontage, a technique pioneered by Dadaists such as Hannah Höch and John Heartfield. However, Stern’s path was soon disrupted by the rise of Nazism. As a Jewish artist, she fled Germany in 1933, eventually settling in Buenos Aires with her husband, the Argentine photographer Horacio Coppola.

Argentina in the 1930s and 40s was both culturally dynamic and deeply patriarchal. While Buenos Aires was a hub for intellectuals and exiles, women remained confined by rigid gender expectations. It was in this climate that Stern received an unusual commission: from 1948 to 1951, she created over 140 photomontages for Idilio, a women’s magazine that ran a column analysing readers' dreams. What began as an editorial project quickly became a radical act of visual protest.

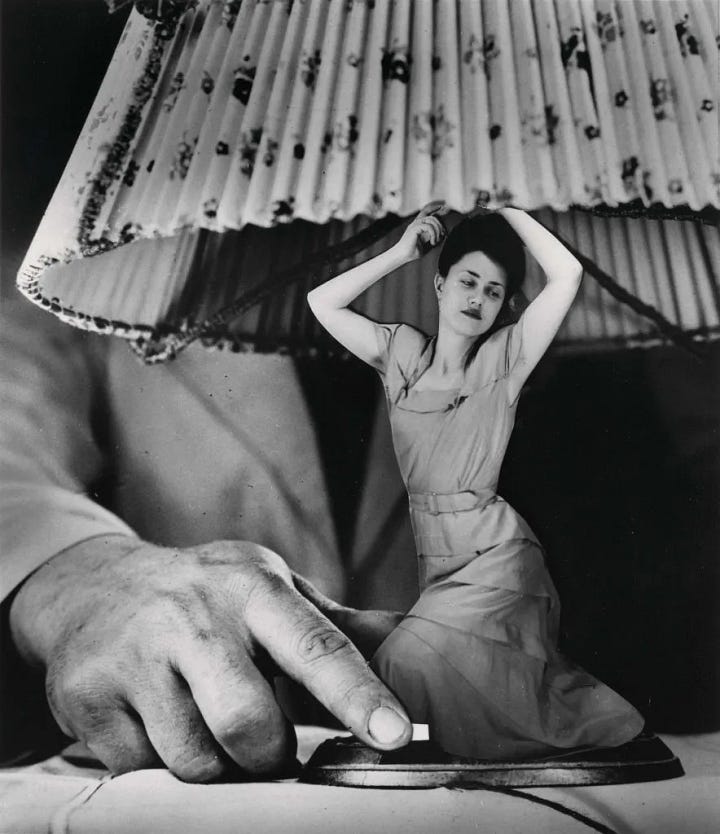

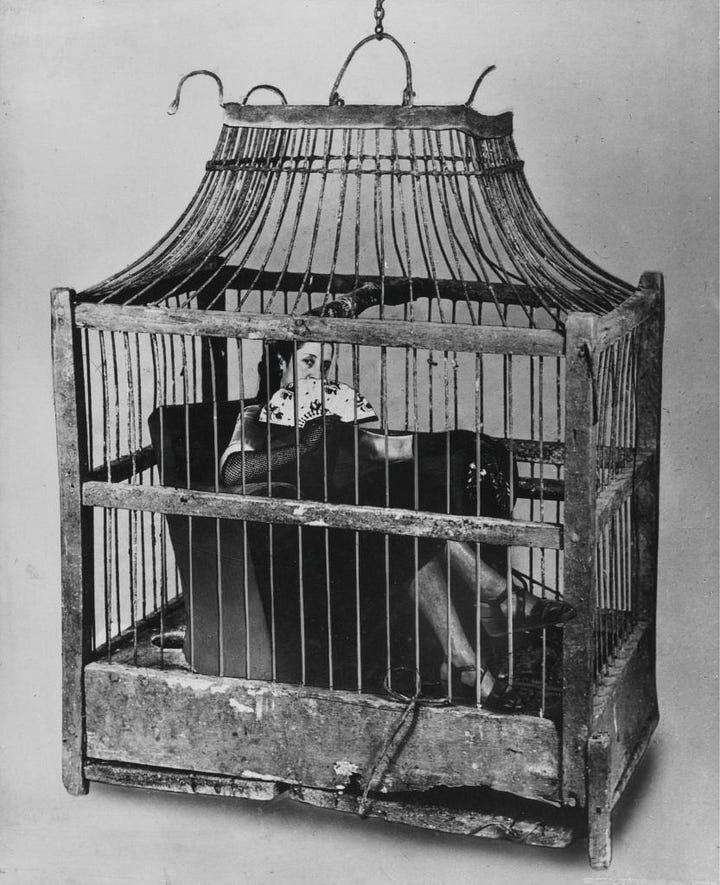

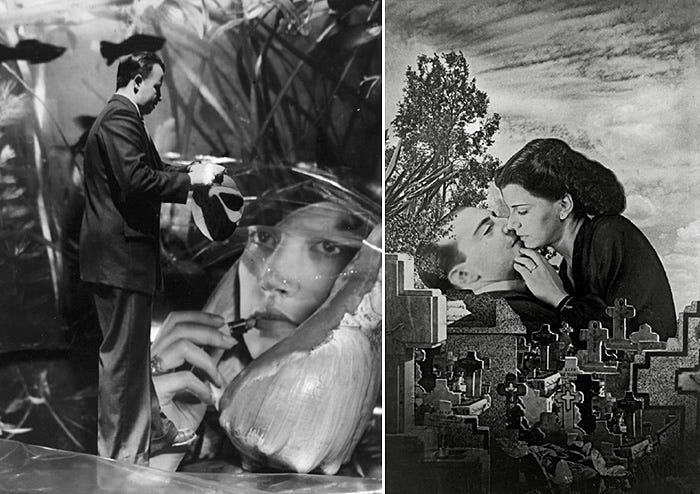

The Los Sueños series reimagines the surrealist dreamscape as a feminist battleground. Unlike male surrealists, who often objectified women as muses or symbols of the irrational, Stern used photomontage to expose the anxieties of real women living within a patriarchal system. Her compositions are striking: in one image, a woman’s head is trapped inside a massive glass bottle, symbolising suffocating domesticity. In another, a house morphs into a cage, reflecting the limited social mobility available to women. In yet another, a woman is shown balancing precariously on an oversized chair, her stability always in question, mirroring the precarious nature of women’s rights at the time.

What makes these images so subversive is their mass appeal. Unlike the exclusive art world, where surrealist works often remained the domain of galleries and intellectual circles, Los Sueños was distributed in a widely read popular magazine. Stern inserted radical imagery into the daily lives of Argentine women, forcing them to confront and decode their own oppression through surreal metaphors. Many readers likely saw fragments of their own experiences reflected in these eerie, dreamlike compositions, even if they lacked the vocabulary to articulate the underlying social critique.

Beyond its feminist implications, Stern’s work is also a testament to her technical mastery. She seamlessly blended disparate photographic elements, manipulating scale, contrast, and composition to create arresting images that feel simultaneously familiar and alien. Her use of photomontage was not merely an aesthetic choice—it was a method of resistance, an artistic language capable of dismantling societal illusions. Unlike traditional photography, which often seeks to capture reality, Stern’s manipulated images questioned reality itself, making the invisible burdens placed upon women starkly visible.

Stern’s engagement with photomontage also positioned her within a broader tradition of politically engaged photography. While artists like John Heartfield used the technique to critique fascism in Germany, Stern applied it to the intimate yet pervasive oppressions of everyday life. This shift in focus—from state power to domestic power—underscores the depth of her vision. She understood that political oppression was not only enacted by governments but also embedded in cultural norms, marriage expectations, and societal roles.

For decades, Grete Stern’s work remained overshadowed by male contemporaries and dismissed as mere commercial illustrations. However, contemporary art historians have re-evaluated Los Sueños as a pioneering body of feminist art. Her photomontages anticipated later critiques of gender roles by artists such as Cindy Sherman and Barbara Kruger, proving that political art could exist outside traditional institutions.

In today’s digital age, where photomontage and meme culture serve as tools of both resistance and manipulation, Stern’s work feels remarkably prescient. Her ability to deconstruct images of femininity and reassemble them into acts of visual defiance remains a vital lesson for artists and activists alike. The rise of AI-generated imagery and deepfakes raises new questions about visual truth and manipulation—questions that Stern, in her own way, was already engaging with decades ago.

Furthermore, the themes Stern explored—domestic entrapment, societal expectations, and the psychological toll of gender roles—remain deeply relevant. Women across the world still navigate pressures to conform, to balance personal ambition with domestic responsibilities, and to push against invisible barriers. Los Sueños reminds us that these struggles are not new, but neither are acts of resistance.

Grete Stern did not just depict women’s dreams—she revealed the nightmares imposed upon them and, in doing so, offered a vision of liberation. In an era still grappling with gender inequality, her images continue to resonate, challenging us to dream not just of escape, but of transformation. Her work is both an artistic triumph and a political statement, proving that even in the realm of dreams, the fight for justice is fiercely real.

FIN.

Thank you for reading this post. If you enjoyed it, please like, comment, share and subscribe. It helps the newsletter grow.

Tres bien , et merci de faire connaitre des artistes méconnus et surtout des femmes

That was such a good read, thank you, Giselle. I’ve never heard of stern before, so thank you for the introduction.

💕