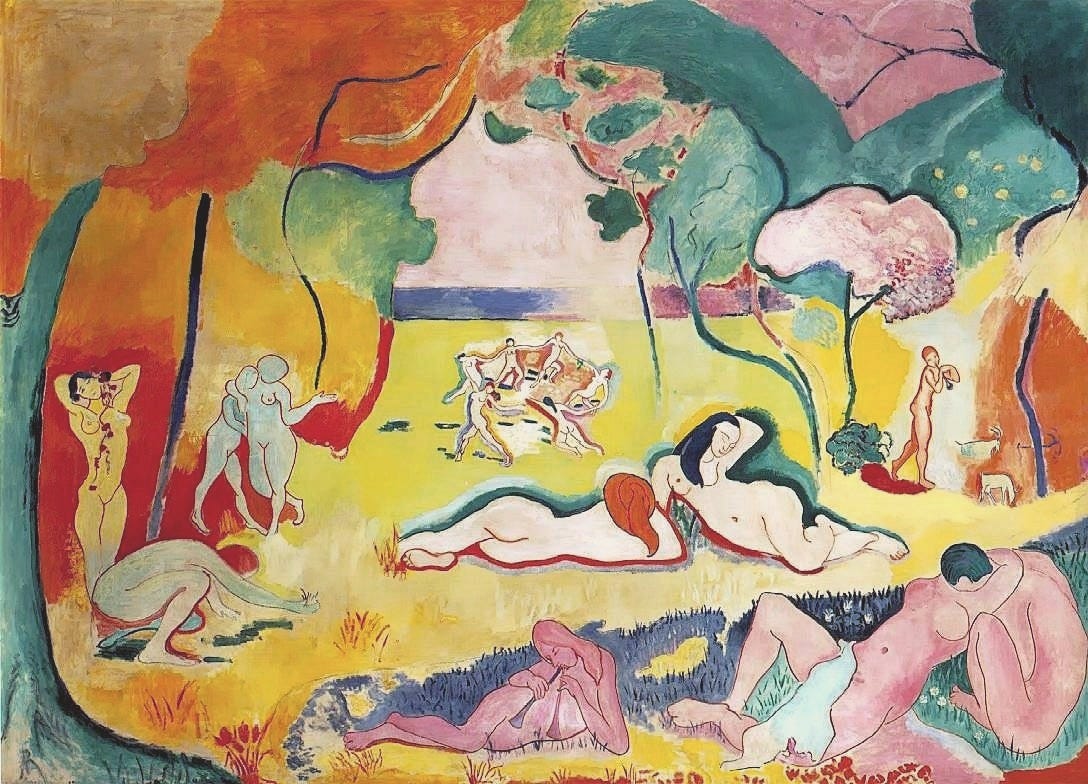

Happy Sunday and welcome back to Giselle daydreams! I wanted to write about Henri Matisse a while ago, but I didn’t manage to do so yet. When I first decide to introduce a new artist here, I usually feature an artwork I particularly admire by the artist in question. In the case of Matisse, Le Bonheur de Vivre is potentially my favourite painting by the French Master.

Le Bonheur de Vivre (The Joy of Life) is one of Henri Matisse's most iconic paintings. Painted between October 1905 and March 1906, it is a vibrant and joyful celebration of life, reflecting Matisse's interest in colour, form, and the emotional power of art.

Le Bonheur de Vivre is a groundbreaking work in modern art due to its vivid colours, bold composition, and fluid, sinuous forms. This painting is an example of Matisse's Fauvist style, where colour is used for emotional expression rather than realism. It also explores several key themes, central to both the painting itself and the broader context of modern art. These themes, all centred around an idealised, utopian vision of human existence reflect Matisse's break from traditional representational art and his focus on emotional expression through colour and composition. Matisse uses these themes to create a harmonious, emotionally resonant vision of life, inviting the viewer to experience the joy, simplicity, and beauty of existence in its purest, most idealised form.

Le Bonheur de Vivre is housed at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia and is considered one of Matisse's masterpieces, capturing his optimistic vision of life and the emotional power of colour and form.

The title, Le Bonheur de Vivre, translates to The Joy of Life, and the scene conveys an idealised, almost mythical vision of human existence. It is set in a dreamlike landscape, where nude figures are depicted reclining, dancing, and engaging with one another in a serene, harmonious setting. The figures are engaged in leisurely, joyous activities—dancing, reclining, playing music—symbolising the pleasures of life. The protagonists appear carefree, interconnected, and euphoric while celebrating life, nature, and sensuality. Matisse wanted to evoke a sense of happiness and emotional upliftment, providing an escape from the complexities and sorrows of modern life. The vibrant colours and rhythmic composition enhance this sense of celebration. The entire scene feels like an idyllic utopia where people can live harmoniously with nature and each other. This focus on joy and sensuality is a response to the pressures and anxieties of modern life, offering an escape into a world of pure, untroubled happiness.

Le Bonheur de Vivre is a seminal work of Fauvism. When first exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants in 1906, the painting provoked both admiration and shock. It was considered revolutionary in its audacity, particularly for its bold use of colour and its break from the established norms of realism. Some critics and artists, including Pablo Picasso, were deeply impacted by Matisse's approach, as it challenged traditional methods of representing space, form, and colour.

In Le Bonheur de Vivre, colour is central to the mood and energy of the piece. Le Bonheur de Vivre does not use colour to represent reality but to convey emotional states. The bright, warm, and sometimes unnatural hues create an atmosphere of joy and warmth, where colour is liberated from realism. The use of vibrant pinks, oranges, yellows, and greens evokes an emotional response that corresponds to the joyous, carefree nature of the scene. In this way, the painting celebrates colour as a primary means of expression, a central tenet of Fauvism.

Colour is the most striking element of this painting, embodying the essence of Fauvism. Matisse uses bold, non-naturalistic colours to create emotional impact rather than to represent reality. Rather than aiming for accuracy, Matisse uses colour to evoke an emotional response, infusing the scene with joy and warmth. The warm colours dominate the landscape, particularly the grass and trees, painted in bright yellows, oranges, and pinks, adding to the feeling of warmth and joy. The figures themselves are painted in similarly vivid tones, with a certain flatness to their forms, emphasising their decorative, non-realistic quality. Complementary colours, such as the cool blues and greens against the warm oranges and pinks, create a lively tension that enlivens the scene. Matisse’s use of colour is not naturalistic but expressive. Each hue seems chosen for its emotional resonance rather than its fidelity to the real world.

The composition is deliberately unconventional, challenging the norms of the Renaissance perspective. The painting depicts a group of nude figures in an idealised pastoral setting, engaging in activities like dancing, playing music, and reclining on the grass. At the centre-right, a group of figures forms a circular dance, a motif Matisse would return to in his later work, particularly in The Dance (1910). This circular form further emphasises harmony and balance in the composition. The scene appears almost timeless and idyllic, evoking a sense of Arcadian peace and joy. In the foreground, reclining figures stretch across the vibrant, warm grass. The middle ground is populated with dancers and musicians, reminiscent of a bacchanal. The figures' poses are fluid and graceful, evoking classical themes of Arcadia, where humans live in harmony with nature, free from the constraints of society. The background shows undulating trees, their forms more suggestive than detailed, under an abstract sky. The figures and landscape flow together in an organic, undulating rhythm. The composition is balanced and harmonious, with large swaths of colour filling the canvas.

The figures are highly stylised, with smooth, flowing lines that reflect Matisse’s desire to reduce forms to their essential elements. The painting has a certain flatness, with little emphasis on perspective or depth. This flatness allows the viewer to focus on the rhythmic quality of the lines and the interactions between colour fields. Matisse rejects the traditional linear perspective in favour of a flat, two-dimensional plane, much like the approach of Post-Impressionist artists like Paul Cézanne. This rejection of depth serves to keep the viewer’s attention on the surface of the painting. Instead, Matisse was influenced by non-Western art, especially African and Islamic art, where abstraction and stylization were more important than mimicking reality. This influence is clear in the way he treats both the figures and the landscape as simplified, ornamental shapes. The figures and landscape elements are arranged in a flowing, organic rhythm. The lines of the bodies echo the curves of the trees and hills, creating a sense of continuity and unity.

The figures are integrated into the landscape, emphasising a connection between humans and nature. The organic, flowing forms of the bodies, trees, and landscape suggest a unity between people and the natural world. The nude figures are not rendered with realistic anatomical precision but are simplified, almost abstract. Their proportions and poses are deliberately stylized to emphasise sensuality and fluidity. There is no separation between figures and the environment; instead, they merge in an idealised, Arcadian vision of paradise. Matisse seems to evoke an ancient or mythical Arcadia, where humanity lives in balance with nature, removed from the stresses of modernity. Each figure engages with the landscape or each other in a relaxed and harmonious way, embodying the joy and freedom suggested by the title.

Nudity is a central aspect of sensual pleasure in Le Bonheur de Vivre. The unclothed figures are depicted without shame or inhibition, celebrating the beauty of the human form in its most natural state. The flowing, curvilinear lines of the bodies, and their relaxed, natural poses emphasise the joy of physical existence. The bodies are stylised, with rounded, flowing lines, suggesting grace and ease. This emphasis on sensuality and the body ties into broader themes of pleasure, liberation, and the joy of existence. By simplifying the human form, Matisse focuses more on the emotional essence of the figures rather than on realistic anatomical detail. Matisse presents the human form not in a realistic, detailed manner but as part of an abstract, decorative scheme, emphasising the idea of pleasure and sensuality over realism.

The idyllic, pastoral setting of the painting evokes timelessness. The figures, landscape, and activities depicted seem removed from any specific time or place, creating a vision of eternal beauty. This contrasts with the industrial and urban concerns of the early 20th century, suggesting that Matisse was seeking to capture something universal and enduring about the human experience. The cyclical nature of life, as symbolised by the dancing figures, reinforces the idea of continuity and timeless joy.

Matisse expresses a sense of freedom—both in the painting’s subject matter and in its formal elements. The figures are liberated from societal constraints, living in a world where joy, love, and community thrive. There’s also a sense of freedom in Matisse’s rejection of traditional artistic conventions, such as perspective and realism, which allows him to explore a more expressive, emotional style.

The theme of community is evident in how the figures interact with each other. Whether dancing in a circle, lounging in pairs, or playing music, the figures are connected to one another, creating a sense of togetherness and mutual joy. This communal celebration highlights the idea of shared human experience and collective happiness, reinforcing the utopian vision. Matisse’s depiction of connection through both physical proximity and shared activity emphasises the importance of relationships in the pursuit of joy and fulfilment.

Matisse’s work draws on the ancient theme of Arcadia, a mythological, idyllic paradise where humans live in harmony with nature. The figures, depicted in a state of naked innocence, suggest a return to a pre-civilised existence, free from social constraints, anxiety, or labour. This idealised vision of nature and human life in perfect unity evokes a sense of timelessness and tranquillity, where the everyday pressures of life are absent. The painting is an expression of joy, sensuality, and peace.

In the centre of the composition is a circle of dancing figures, a motif Matisse would revisit in later works like Dance (1910). The dance symbolises pure, ecstatic joy and communion between the figures. Their rhythmic movement creates a sense of vitality and celebration. The presence of music further reinforces this idea, representing creativity and the arts as natural, joyful expressions of human existence.

The close interaction between the figures and their lush, vibrant surroundings expresses a sense of unity with nature. The natural setting, painted in soft, warm colours, seems to embrace the figures, with trees, grass, and sky forming a harmonious background for their peaceful activities. Matisse’s integration of the human form with the landscape symbolises a seamless bond between humanity and the natural world, aligning with pastoral and utopian ideals.

Fauvism, characterised by its bold use of colour and a liberation from traditional representational art is fully realised in Le Bonheur de Vivre. This work marked Matisse as a leader of the Fauvist movement, which prioritised emotional expression through colour. The painting emphasises colour as a means to convey meaning, independent of the actual subject. The simplified, almost abstract forms in the figures and landscape reflect Fauvism’s break from representational art. Matisse uses these forms to convey a sense of ease and joy rather than focusing on detailed realism.

Le Bonheur de Vivre stands in stark contrast to the art of the time. In contrast to the dark, sometimes pessimistic realism of the late 19th century, Matisse offers a radiant vision of life’s pleasures. Matisse draws on classical themes, particularly the timeless motifs of pastoral life and classical nudes. However, he transforms these traditional subjects through his modern, abstract style. While the figures and landscape may recall the work of classical painters like Titian or Poussin, Matisse’s treatment of colour, form, and composition breaks with tradition to create a fresh, modern interpretation of timeless themes. Matisse’s simplified, almost childlike forms and the wild, exuberant use of colour mark a radical break from tradition. In rejecting naturalism, Matisse opened the door to abstraction. His emphasis on colour and form over content would influence many modern movements, including Expressionism and Abstract Expressionism.

Le Bonheur de Vivre is often compared to works by Paul Cézanne and Gustav Klimt. Cézanne’s influence can be seen in the structure and geometry of the landscape, while Klimt’s decorative, pattern-like use of colour may have inspired the flat, vivid areas of Matisse's painting. Additionally, it prefigures Matisse’s own future works, especially the famed Dance series. The circular dancing figures in Le Bonheur de Vivre would evolve into one of Matisse’s most iconic motifs.

While modern life at the time was marked by industrialisation, urbanisation, and a growing sense of alienation, Matisse’s painting offers a form of escapism. It provides a visual antidote to the chaos and hardships of the early 20th century, presenting a peaceful, harmonious alternative. The emphasis on a timeless, pre-industrial existence reflects Matisse’s desire to use art as a source of refuge and comfort.

At the time, Le Bonheur de Vivre was highly controversial for its bold use of colour and its lack of traditional perspective. However, it has since come to be recognised as one of Matisse’s masterpieces, symbolising his vision of art as a source of pleasure, emotional expression, and personal freedom. In the long run, this painting laid the foundation for modern art’s shift away from depicting reality and toward conveying emotion and ideas through abstract form and colour.

Le Bonheur de Vivre stands as a pioneering work in early 20th-century art, laying the groundwork for the further abstraction that would come to define modern art. Matisse draws upon classical themes of pastoral and Arcadian settings, referencing ancient Greece and the ideal of human beings living in balance with nature. The joyous and idyllic tone contrasts sharply with the more industrialised, modern world of the early 20th century, offering a retreat into an almost timeless utopia. Through its radical use of colour, simplified form, and dreamlike composition, the painting exemplifies the ideals of Fauvism and remains a celebration of life's joys and sensual pleasures.

I hope you enjoyed today’s post.

Giselle xx

Love this.

I feel like this painting captures so many different elements of Matisse's vision all at once, it can be hard to know where to start with it all. But you write so wonderfully, and cover so much detail - it really was a joy to read.

Keep up the great work.