Venus through the Ages: beauty, art, and the everlasting muse

The many faces of Venus: similarities, differences, and modern relevance

Happy Sunday and welcome back to Giselle daydreams! First, I have an exciting announcement. I’ve officially launched my conscious fashion label Neithé Atelier grounded in luxury and using fabrics such as silk, linen and cotton. For those interested, head over to Neithé Atelier.

Second, Giselle Daydreams is my passion project, and I still intend to publish interesting and thought-provoking content. Hence, I decided to keep posting weekly when time allows or less often on busier periods.

Without further ado, let’s dive into today’s post. I decided to write about the depictions of Venus through the Ages and explore how different artists portrayed this beautiful and everlasting muse.

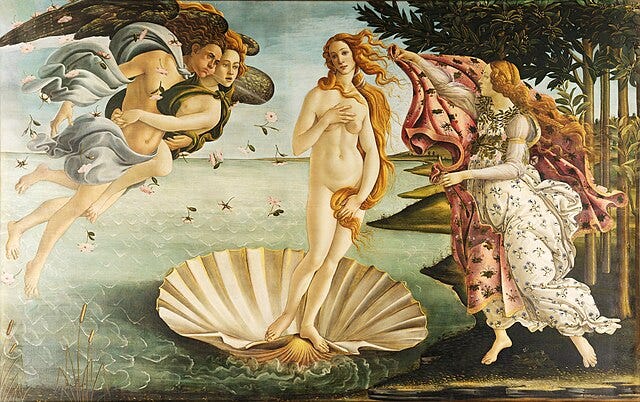

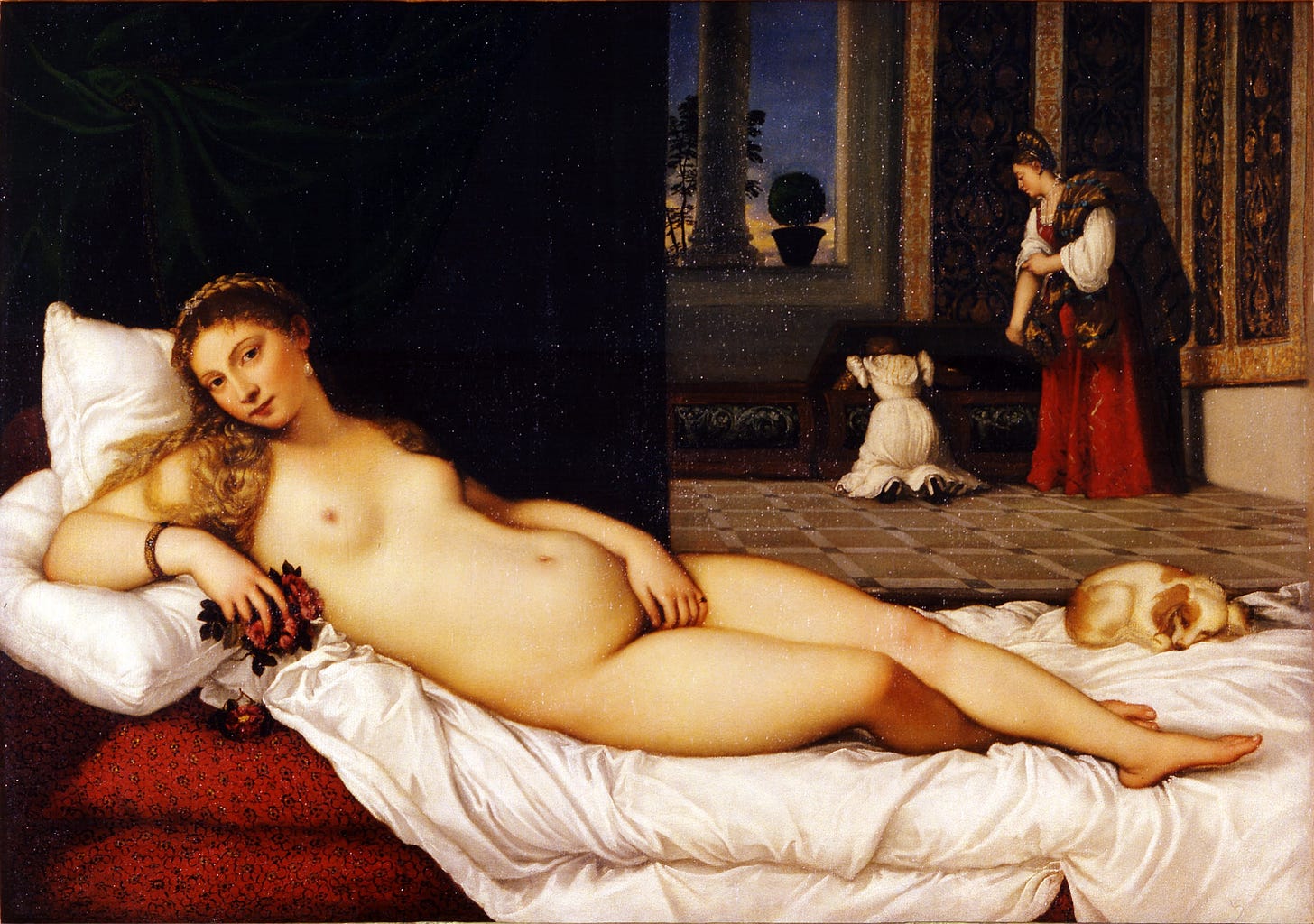

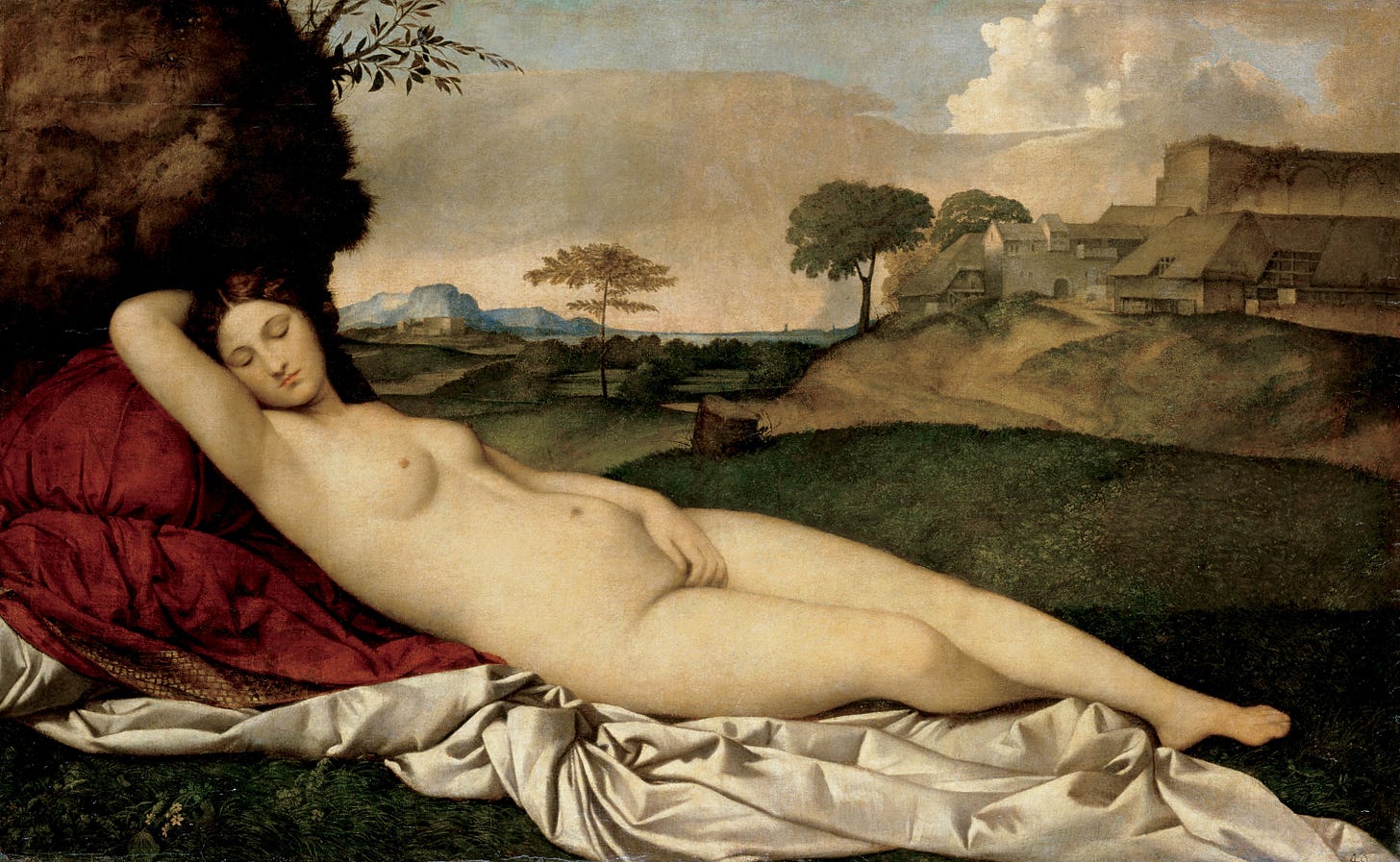

Throughout art history, the goddess Venus in Roman mythology has been an enduring symbol of beauty, love, and sensuality. Artists from different eras have depicted her in various ways, each reflecting the cultural ideals and artistic movements of their time. I decided to explore six of the most famous paintings of Venus — Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–1486), Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1534) and Venus and Adonis (1554), Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (c.1510; completed by Titian), Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (1647-51) and François Boucher’s The Toilet of Venus (1751) — analysing their similarities and differences, uncovering fascinating details, and discussing their lasting relevance in today’s society.

A common thread among these depictions is the representation of Venus as the epitome of feminine beauty. Each painting showcases a nude or partially nude Venus, emphasising ideals of physical perfection and sensuality. The compositions often feature soft, flowing lines and a dreamlike quality, inviting viewers into a world of idealised beauty and mythology. This idealisation reflects the period’s societal norms regarding female beauty, reinforcing contemporary expectations of grace and harmony in the human form.

Another recurring motif is Venus's association with love and desire. Whether she is portrayed as a divine being emerging from the sea (The Birth of Venus), as an object of earthly love and seduction (Venus of Urbino), or in a moment of longing (Venus and Adonis), her presence in these paintings consistently conveys an emotional and symbolic connection to passion, romance, and allure. These depictions serve not only as artistic expressions but also as reflections of how different societies have interpreted love and femininity across time.

The Birth of Venus embraces the idealised beauty of the Renaissance, with a graceful, elongated figure and ethereal presence. This portrayal aligns with the Neoplatonic philosophy of the time, which emphasised divine beauty as a reflection of higher truths. In contrast, Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus presents a more naturalistic and intimate portrayal, with Venus gazing at herself in a mirror, adding an introspective dimension. This shift from divine abstraction to personal realism reflects the broader transition in European art towards a more human-centred approach to beauty and identity.

Titian’s Venus of Urbino is a clear example of the Venetian tradition of eroticism, with Venus reclining in a suggestive pose, engaging the viewer with a direct gaze. The contrast between her gaze and the soft domestic setting adds layers of intimacy and seduction. Similarly, Boucher’s The Toilet of Venus leans into Rococo sensuality, portraying Venus in a playful and indulgent setting, reinforcing the aristocratic fascination with pleasure and flirtation. In contrast, Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus is more serene and contemplative, her nudity appearing less provocative and more in harmony with nature. This variation highlights how different artistic movements approached Venus not only as an object of beauty but as a subject shaped by societal attitudes toward femininity and sexuality.

While some paintings focus solely on Venus herself (The Birth of Venus, Sleeping Venus), others place her within a dramatic scene. Titian’s Venus and Adonis is unique in its dynamic storytelling, depicting Venus desperately trying to hold back her beloved Adonis before his fateful hunt. This moment of emotional intensity stands apart from the more static and meditative depictions of the goddess. The contrast in compositions between solitary Venus figures and those engaged in dramatic interactions reveals how artists have used mythological narratives to evoke deeper emotional connections with viewers.

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is believed to be one of the first large-scale paintings of a mythological nude in Renaissance art. Unlike most Renaissance works, it was painted on canvas rather than wood, which was unusual for its time. The painting was likely inspired by classical sculpture and poetry, emphasizing Venus as both an artistic and philosophical ideal.

Titian’s Venus of Urbino was commissioned as a wedding gift, symbolising marital love and fertility. The small dog at Venus’s feet is often interpreted as a symbol of fidelity, yet the provocative pose of Venus adds an intriguing tension between purity and sensuality.

Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus was left unfinished upon the artist’s death and later completed by Titian, who added the landscape background. This collaboration demonstrates the transition from Giorgione’s lyrical idealism to Titian’s more grounded realism.

Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (also known as Venus at her Mirror ) is one of the few surviving female nudes from Spanish Baroque art. The painting was famously slashed by a suffragette in 1914 as a protest against the objectification of women, highlighting its continued role in debates about female representation.

Boucher’s The Toilet of Venus was commissioned by Madame de Pompadour, the mistress of King Louis XV, further linking Venus to themes of power, beauty, and influence. The painting reflects Rococo's excess, with its emphasis on luxury and ornamental beauty.

The portrayal of Venus in these masterpieces continues to resonate today, particularly in discussions surrounding beauty standards, the male gaze, and the evolving representation of femininity. While these paintings celebrate idealised beauty, they also raise questions about objectification and societal expectations of women. Contemporary artists often reference these works in critiques of traditional beauty norms or reinterpret Venus through a modern lens, highlighting diversity and shifting ideals.

Furthermore, the theme of self-reflection The Rokeby Venus remains particularly relevant in an age dominated by social media and curated self-images. Just as Venus gazes into the mirror, people today engage in self-presentation and self-exploration, questioning how beauty is perceived and valued. The tension between admiration and self-critique in these paintings mirrors today’s conversations about body image and self-perception in the digital age.

From Botticelli’s divine vision to Velázquez’s introspective realism, the many faces of Venus reveal much about changing artistic styles and cultural ideals. These paintings continue to captivate audiences, offering timeless reflections on beauty, love, and the human experience. Whether as a symbol of divine perfection, sensual desire, or personal introspection, Venus remains as relevant today as she was centuries ago, proving that art’s dialogue with beauty and identity is never-ending.

FIN.

Cool article, Giselle! I was lucky to see The Birth of Venus at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence several years ago. It was early morning and I got to just stand and look it for ages.

Good read, thanks!

Personally, I love the Venus of Willendorf. Just last year I discovered, that the symbol of femininity (Venus) is now even in the jewellery-art of Carina Hardy :) She also made a collection on Gustav Klimt, which I love