Marlow Moss: Breaking Grids and Shaping Modernism

Exploring the Bold Vision of a Trailblazing Artist at the Intersection of De Stijl and Constructivism

This post might be too long for your mailbox, please move on your browser or via the Substack app to read the entire post.

Happy Sunday and welcome back to Giselle daydreams! Today, I decided to feature Marlow Moss, a trailblazing artist who may not be as well-known as her male counterparts but who is worth discovering.

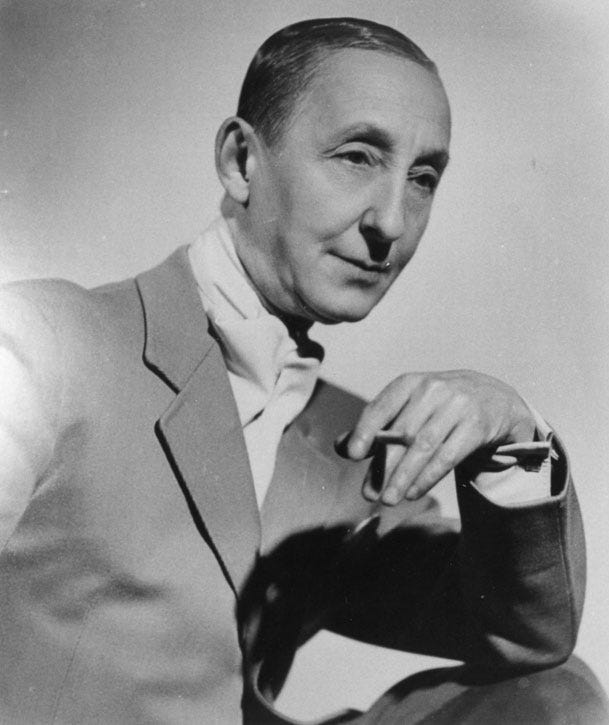

Marjorie Jewel Moss was born in 1889 in Kilburn, London. She came from an upper-middle-class Jewish family. In 1919, she changed her name to Marlow and adopted a gender-neutral presentation. This was an act of self-determination, challenging societal norms around gender and sexuality at a time when such decisions were rare and often stigmatised.

Moss was a pioneering British artist and a key figure in modernist art, known for her contributions to abstraction and constructivism. Despite being less well-known than many of her contemporaries, her work has gained recognition recently for its innovation and influence.

Moss was a non-binary lesbian, which further set her apart in conservative British society. She lived openly as a gender-nonconforming individual, changing her name from Marjorie Moss and adopting a masculine style of dress. This choice reflected her broader nonconformity, both in life and art. She spent much of her life with her partner, the Dutch writer and art historian Netty Nijhoff.

“I am no painter, I don't see form, I only see space, movement and light.”

This statement, as recalled by her partner A. H. Nijhoff, captures Moss's distinctive artistic vision, highlighting her emphasis on spatial dynamics and the interplay of light rather than traditional form.

After studying at the Slade School of Fine Art, she moved to Paris in 1927, seeking freedom and creative inspiration. She studied at the Académie Moderne, run by Amédée Ozenfant and Fernand Léger, and immersed herself in the thriving avant-garde scene. Her relationship with De Stijl and Constructivism is fascinating because her work straddles these two influential movements while maintaining her own distinct voice.

Marlow Moss's life and work are deeply intertwined, reflecting her defiance of convention and her commitment to innovation. Her life as a gender-nonconforming, queer artist informs her work, which challenges notions of rigidity and balance. Both aspects of her story resonate today as society reexamines voices that were once overlooked.

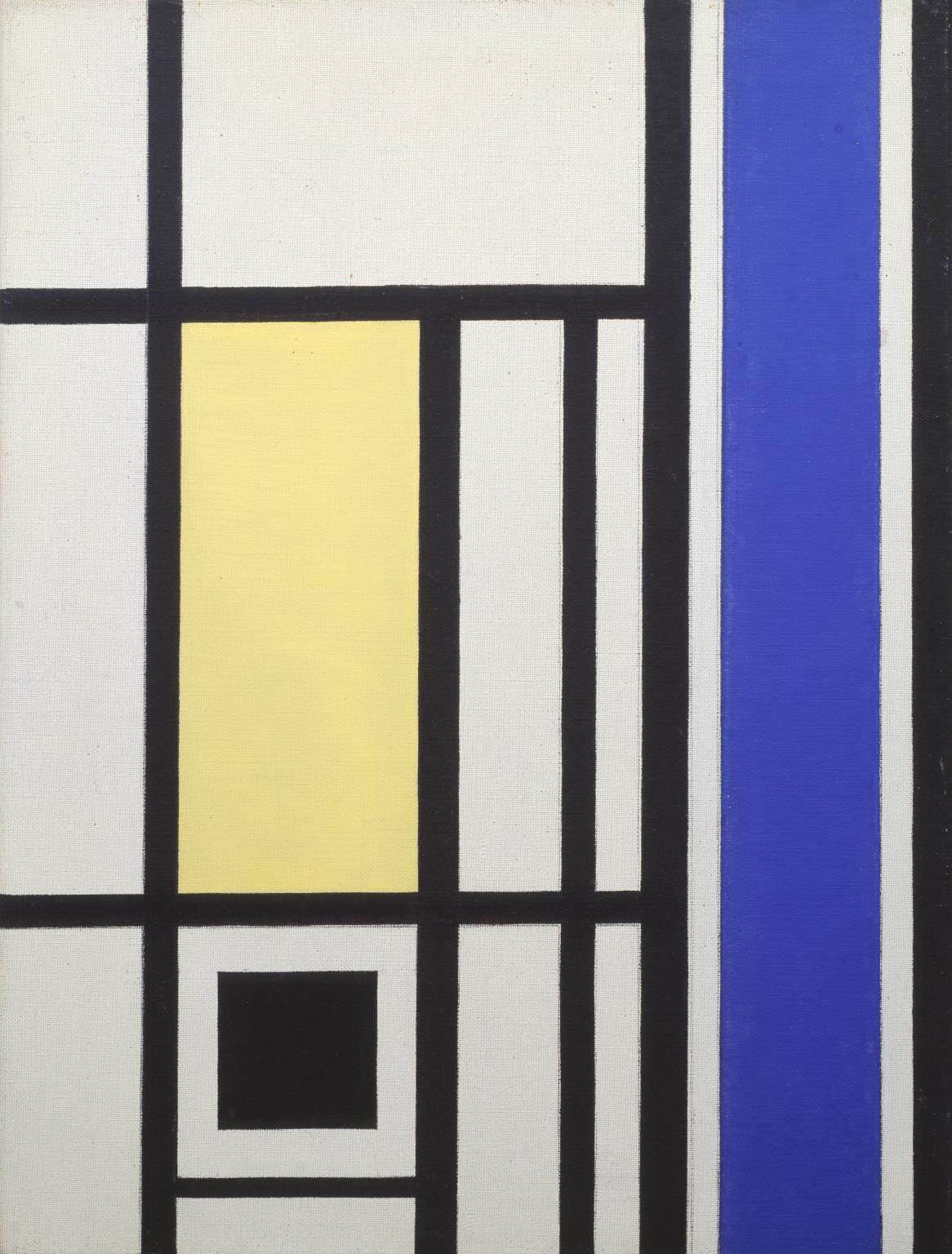

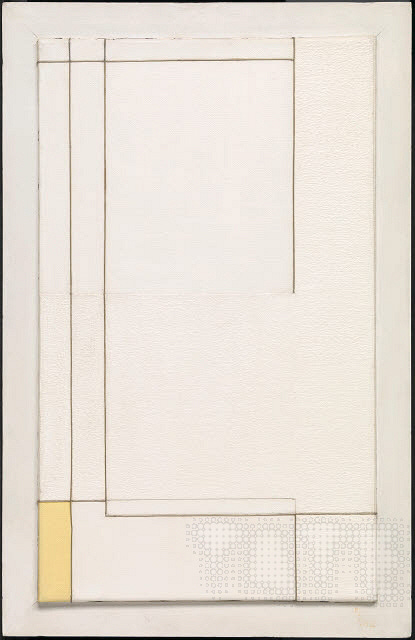

De Stijl, founded in 1917 in the Netherlands, was a movement focused on universal harmony and order through abstraction. Its most prominent figures were Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, and its aesthetic was defined by straight lines, primary colours, and right angles. Moss was heavily influenced by De Stijl’s commitment to geometric abstraction and its rejection of representational art. She adopted the grid as a fundamental structure in her work, exploring its capacity to create visual order. Like Mondrian, Moss used a restrained palette, favouring black, white, and occasionally primary colours, though her work leaned more toward monochromatic schemes. Moss's work is rooted in geometric abstraction and constructivism, marked by clean lines, grids, and dynamic compositions.

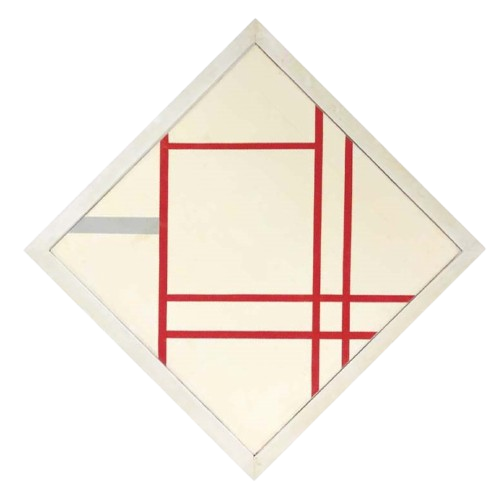

Moss admired Mondrian and established a working relationship with him in Paris during the late 1920s and 1930s. They exchanged ideas, and Moss even studied his techniques. However, their relationship was complex. Mondrian reportedly viewed Moss as a promising disciple but did not fully embrace her innovations, which he may have seen as diluting the purity of his vision as she departed from his orthodoxy.

Moss shared stylistic elements with De Stijl; but introduced key innovations. Unlike Mondrian's single lines, Moss introduced parallel double lines, which created rhythm and movement in her compositions. Mondrian, who adhered to strict singularity in his lines, saw this as a deviation. While Mondrian sought balance and equilibrium, Moss embraced tension and asymmetry, pushing the boundaries of the grid. These latter often disrupted the viewer’s expectations, making her work more dynamic than Mondrian’s carefully balanced compositions. Moss developed a distinct abstract style, often using geometric forms, lines, and grids. Her work reflects the influence of Dutch De Stijl artists like Piet Mondrian, but with a unique twist that incorporates dynamic movement and variation.

Moss was influenced by Mondrian and shared his interest in primary colours and straight lines. However, she often diverged by introducing double lines and asymmetry, breaking away from Mondrian's strict orthogonality. These innovations placed her on the fringes of De Stijl, as she was less dogmatic in her approach than her contemporaries.

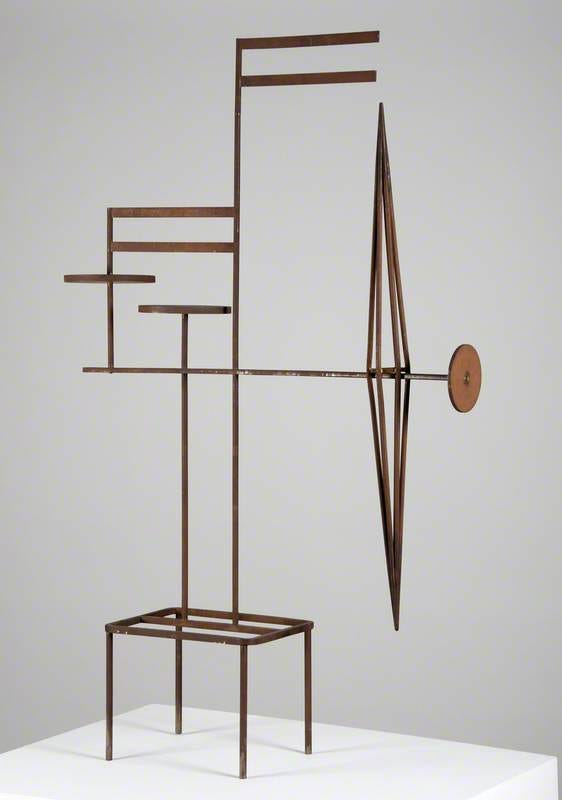

Constructivism, emerging from revolutionary Russia in the 1910s, emphasised functional art, industrial materials, and the integration of art with everyday life. The movement’s key figures included Vladimir Tatlin, Kazimir Malevich and El Lissitzky. Moss shared Constructivism’s fascination with modernity, precision, and the use of industrial materials. Moss’s work retained the Constructivist focus on creating universal forms that transcended individual expression. She often worked with oil on canvas but also explored reliefs and sculptures, experimenting with industrial materials like Perspex (an early form of acrylic glass) and metal, pushing the boundaries of traditional media. These materials aligned with her interest in modernity and precision. Her sculptural reliefs reflect a Constructivist ethos, combining geometry with three-dimensionality to explore the interplay of light, shadow, and materiality. However, her approach was more intuitive and less overtly political than Russian Constructivism. Where Russian Constructivists often tied their art to the ideals of socialism and industry, Moss's work focused on abstraction as an exploration of visual and spatial relationships.

Moss’s work embodies a hybrid of Constructivism and De Stijl, combining the latter’s emphasis on flat grids and primary colours with the former’s exploration of materials and spatial dynamics. Moss used De Stijl’s static grid as a starting point but broke it open with Constructivist-inspired movement and materials. By creating reliefs and experimenting with industrial materials, Moss pushed abstraction into the third dimension, a space where Constructivism thrived. This synthesis allowed her to innovate beyond the confines of either movement, creating work that feels simultaneously rigorous and dynamic. For Moss, abstraction was more than a visual language — it was a reflection of the modern world's order and chaos. She viewed art as a means of understanding universal structures, blending logic with creativity. Furthermore, as a queer, gender-nonconforming artist, Moss’s work inherently challenges the traditional narratives of these male-dominated movements.

The outbreak of World War II forced her to leave France and disrupted her career. Moss and Nijhoff relocated to Cornwall, England, where Moss continued her artistic practice in relative isolation. After the war, her work did not receive the same recognition as some of her contemporaries, but she persisted, dedicating herself to her vision until her death in 1958.

In recent years, Moss's work has been rediscovered and celebrated. Today, her work is recognised as a vital link between these two movements, bridging Mondrian’s rigorous grids and the Constructivists’ exploration of materials and spatiality. Exhibitions like Mondrian and His Studios (Tate Liverpool, 2014) and others have revisited her contributions, highlighting how she expanded the language of abstraction. Moss’s position at the intersection of De Stijl and Constructivism allowed her to innovate in ways that either movement could on its own.

However, this same hybridity made her difficult to categorise, contributing to her marginalisation during her lifetime. Despite her contributions, Moss struggled with invisibility, overshadowed by figures like Mondrian and Malevich. Her gender identity and queerness, combined with her choice to live outside major art centres post-war, contributed to her marginalisation.

Today, Moss is celebrated as a nonconformist trailblazing modernist artist and the first British Constructivist artist who challenged conventions in both her art and personal life. Her contributions to abstract art have been increasingly acknowledged, and her work is now featured in major collections, such as the Tate and the Kröller-Müller Museum.

As always, thank you for reading. Giselle xx

Fascinating how she who masterted two of main strands of moder abstract art could be shoved by into darkness.

This was super interesting! Thank you for that💛